Top 5 Lessons from working in VC

Lesson 1: Not all that glitters is gold

To an average bystander it is easy to assume that venture capitalists spend their time looking at sexy companies that make headlines such as Snapchat or Blue Apron, but rather the opposite is true. Most of the companies VCs look at are not the ones you read about in the news, but are never-the-less important companies in their particular niche.

Take for example a company called Amplitude, that my firm Silicon Badia was an early investor in. The company provides product managers and engineers with data on user engagement and retention, empowering developers to make better products that captivate us and provide a better user experience.

Although Amplitude is not a company you would talk about at the dinner table, it serves an important function to companies such as Microsoft, Venmo, and Udacity. Our venture firm saw the value in Amplitude early on and became a seed stage investor, and I am proud to announce that they just closed a $30 million series C round, with big name investors such as Benchmark Capital and Battery Ventures.

Which brings me to my next point…

Lesson 2: The types of VCs

There is no magic formula to decide which VC is right for which entrepreneur, but there are important factors to consider. First is the misconception that having bigger investors is always better. If your only goal is money then perhaps this may be the case (although even then I have reservations). The truth is each type of VC has something to offer.

Small VC: A small VC may not write a million dollar check, but they will be there for you if you need to raise one, and will not hesitate to make the introductions to other investors to help you close a round. Furthermore, these firms tend to be more involved with their portfolio companies and offer funding, but also support, recruiting, and a network of companies, individuals, and investors that can help your company succeed. Sometimes small VC firms are general funds, but often they have a specialty such as biotech, fintech, or agtech.

Bigger VCs tend to take a more portfolio approach (although this is not always the case), and tend to be more hands-off. This is not inherently good or bad, just different and up to the preferences of the entrepreneur. Large VCs tend to write higher check sizes, take more equity, and have a larger network. If the VC is a brand name it will also help get others investors interested because of FOMO (fear of missing out), despite this alone being a poor reason to invest (as each company should be evaluated on its merits alone).

Corporate VCs — These are a different kind of animal altogether. In some ways they are similar to large VCs, but differ in goals. While normal VCs goal is to make returns for their investors (limited partners), a corporate VC is more interested in acquiring technology for their parent company. Examples include Microsoft’s venture arm, GE ventures, and Intel Capital. These serve more as replacements to R&D in instances where the parent company views it as advantageous to acquire the tech/talent rather than build it in-house. Usually these VCs take a much larger controlling stake in investments and focus on companies that are likely acquisitions for their parent company.

Lesson 3: The Work of a VC

To somebody who watches Shark Tank or Planet of the Apps, it is easy to think that VCs spend their time sitting in chairs while companies pitch to them for 5 minutes and make an instant decision that determines the future of their company. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

In reality, the process is likely to take a few weeks at the very least. VCs rarely, go in blind and listen to a pitch without knowing anything about the company beforehand. It is usually the case that the VC has done extensive homework on the company beforehand, and dug into the industry and competition. It is usually after all this research that the VC would listen to, or more likely, read the pitch deck of a company. The process is much more of a back and forth between the entrepreneur and the investor, and feels much more like a conversation than the antagonistic relationship portrayed by the media.

So what did I do as a VC analyst this summer? Although cliche, I am happy to say that no day was ever the same. VC is easily one of the most intellectually stimulating jobs I ever had the pleasure of doing.

One week I was learning everything there is to know about APIs (application programming interface) — which are basically developer tools that access a program on behalf of a user. For example, Twitter offers an API that allows developers to create insights based on Twitter’s wealth of data, ex. analysis of personality traits between two users. After learning about the API economy, the next week I was assigned to a project dealing with the potential of vertical farming to impact food scarcity in urban areas, and the next week I was learning about blockchain’s potential to cut costs for financial institutions for derivates and over-the-counter trading.

One of the most interesting projects I dealt with was a company that is serving the underbanked communities in Uganda and Tanzania, a population that is middle class, owns smartphones, and has banking services, but do not typically access it due to costs and/or lack of availability. The company, called Wala, (now a public investment our firm made), created an smartphone app that serves as a white label for banks in the area to service their underbanked customers.

I am proud to say that our firm decided to invest in this company, and it serves as a reminder of why VCs do what they do. Technology has such an important potential to improve lives, and VCs help these technologies make it into the hands of consumers and improve their quality of life.

Lesson 4: Ask 5 VCs for an opinion, get 7 answers

In VC one is never always right, in fact the model of VC takes into account that most investments will not be homeruns, a few will be triples or doubles, and most will be singles or strike outs completely.

Very few investors thought the idea of strangers living in your home would be successful, and AirBnb was laughed out the door. The point being if you ask 5 VCs for an opinion on a company, you will get 7 different answers. So as an entrepreneur there are a few things you should take from this. The first being if you are rejected by a VC, to not take it personally. Just because one VC did not realize the potential of your company does not mean it is not a strong company, it could just be that the VC did not know enough about the area, could not see a way to build value, or frankly, made a bad decision, it happens. On to the next one. There will be a VC somewhere who will see your genius, and if not, prove them wrong, and eventually investors will be at your doorstep begging to fund you.

On the VC end of things, there is rarely a consensus amongst an investment committee about a decision to invest, especially for the best companies. These are the companies that are controversial, and unorthodox, yet see something in the world that does not yet exist, and wish to make it so. My managing partner and I, had many debates, and it is through these debates that we truly saw the merits and flaws of different companies.

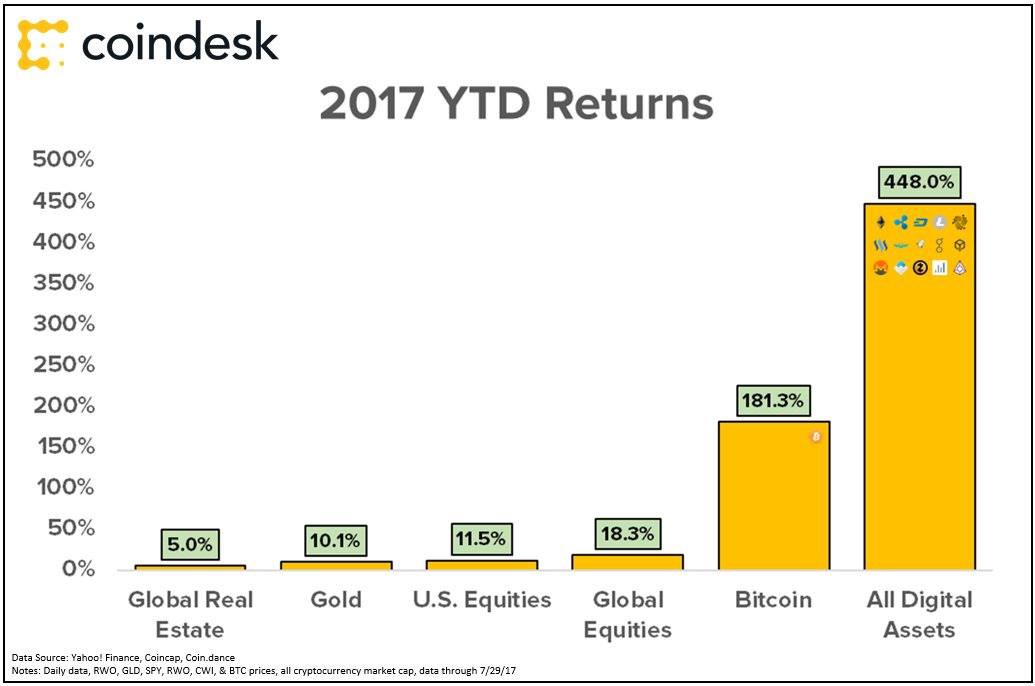

One of the many debates we had was on the ICO economy. Is it a bubble? Is it the next internet? If it is, will it produce Amazon … or Pets.com? After extensive research and learning about ICOs and the underlying technology blockchain, we became convinced that the Web 3.0 (decentralized web) is a serious value add in the right circumstances. There are some ICOs that are taking advantage of this value proposition, however, truthfully these are the minority of ICOs. The majority are selling snake oil. So how do we, a busy generalist VC, gain exposure to the tremendous potential and gains of ICOs, while maintaining quality and ensuring each company is the real deal?

We discovered the answer in our next investment, Pantera Capital. Pantera is a VC and hedge fund that is opening an new fund dedicated to ICOs, they have an investment team trained in studying the cryptocurrency market and analyzing which of the initial coin offerings are substantive companies that will exist in a few years, and which are strong at marketing, but lacking in substance.

The Pantera Capital ICO fund will allow our VC to gain exposure to this 448% gain in YTD returns from an expert team, while mitigating risk for our investors, and allowing us as a VC to spend our time focusing on our speciality: early stage companies

Lesson 5: Hard, Meaningful, Work

The last, and most important lesson I took away from working in VC, is how hard the work is. Investors, often get called out for riding on others blood, sweat, and tears. Entrepreneurs do all the work, and VCs get all the money. While it is true, entrepreneurs do so much admirable work, and their dedication to their companies is inspirational, it is also true that VCs work just as hard and provide an equally vital role in the startup ecosystem.

Unfortunately capital is limited, and VCs can’t invest in every idea that walks in the door, even some of the good ones (poor mandate fit, conflict with existing investments, etc.). Furthermore just as we are investors in companies, we have investors too, and we have an fiduciary responsibility to give them returns. So our decision to invest often follows different factors, such as thesis and mandate fit, diversification, and risk.

Saying no to companies is easily the hardest part of the job. It is hard telling companies that we decided not to invest in their company, especially when a founder put so much hard work and passion into it. But when I say no it does not usually mean the company is a bad company, as rarely do we get far with any “bad” companies.

Usually the hard companies to say no to are the ones that are in-between. They could very easily be a good company, but for one reason or another we decided not to invest. It could just be that the timing was not right, and it was too early, in which case we would stay in touch with the entrepreneur and come back later once there is more progress. It could be that it was too similar to existing investments and we needed more diversification. It could be a number of factors. We try to be as helpful as possible with rejection, and offer suggestions for the future. Rejection is not the end of success, it is a pivotal step on the path to it.

For the companies that do receive venture funding, it is a tremendous feeling helping companies grow and helping founders turn their dreams and ambitions into a reality. That is really what motivates me when I woke up each day this summer, knowing that my work is helping somebody’s dream become successful. VC is not about being the star of the show, it is a supporting role, but it is one I love playing. I have a front row seat to the most interesting people in the world, entrepreneurs, and I get to watch them do what they love and care about, and learn from them about new industries, topics, and problems that they are solving.

I would like to thank the team at Silicon Badia, and especially my managing partner and mentor, Namek Zu’bi, for giving me this experience this summer. Not many VCs would have given me the chance they did, but they allowed me to prove myself to them, and I worked my butt off everyday to thank them for that chance. Namek made me work harder than any boss or professor I ever had, and there was not a single dull moment at Silicon Badia, but it was all worth it. I came out smarter, stronger, and wiser.

Venture is hard work, but I am glad I got the chance to do it, and I hope this is just the beginning of a lifelong career in helping entrepreneurs on the path to success. got the chance to do it, and I hope this is just the beginning of a lifelong career in helping entrepreneurs on the path to success.

My boss, mentor, and role model: Namek